Redpanda vs. Kafka: comparing architectures, capabilities, and performance

The main difference between them? Kafka is an established Java-based data streaming platform, with a large community and a robust ecosystem. Meanwhile, Redpanda is an emerging, Kafka-compatible tech written in C++, with an architecture designed for high performance and simplicity.

Introduction

Since its inception, Apache Kafka has firmly established itself as the de facto standard for data streaming. But it’s not the only technology you can use to work with streaming data. One of the alternatives is Redpanda, an emerging platform that provides compatibility with the Kafka protocol.

This blog post compares Kafka and Redpanda, by looking at their architectures, features, and performance characteristics. Before we dive into a detailed head-to-head comparison, here are some key takeaways:

- They’re both distributed pub/sub platforms, but they have different underlying architectures.

- They offer similar messaging features, but Kafka has superior native stream processing capabilities.

- Redpanda and Kafka are scalable platforms that provide low latency and high throughput. Redpanda theoretically offers better performance, but it’s best to run your own benchmarks to see which one is best suited to your specific use case and workload.

- Kafka provides a richer ecosystem of integrations and has a larger community, while Redpanda comes with a simpler, less complex architecture.

If you’re here because you’re planning to build an event-driven application, I recommend the “Guide to the Event-Driven, Event Streaming Stack,” which talks about all the components of EDA and walks you through a reference use case and decision tree to help you understand where each component fits in.

What is Apache Kafka?

Apache Kafka is a data streaming platform written in Java and Scala. It’s designed to handle high-velocity, high-volume, and fault-tolerant data streams. Kafka was originally developed at LinkedIn and later donated to the Apache Software Foundation. Kafka has quickly become a popular choice for building real-time data pipelines, event-driven architectures, and microservices applications.

What is Redpanda?

Redpanda (formerly Vectorized) is a data streaming platform developed using C++. It’s a high-performance alternative to Kafka that provides compatibility with the Kafka API and protocol. In fact, if you look at Redpanda’s website, you’ll get the feeling it’s a simple, cost-effective drop-in replacement for Kafka. Similar to Kafka, Redpanda is leveraged by businesses and developers for use cases like stream processing, real-time analytics, and event-driven architectures.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: architecture

Redpanda and Kafka are identical in some regards:

- They are distributed systems.

- Both have the concepts of producers, consumers, and brokers. Producers generate data and send it to brokers, while consumers read the data ingested by brokers.

- Redpanda and Kafka use topics to organize data. Producers write data to topics within brokers, and consumers read data from topics. Note that topics are multi-producer and multi-subscriber: a topic can have one or more producers that send messages to it, and one or many consumers that subscribe to it to receive messages.

- Topics are split into partitions, which can be spread across multiple nodes. Partitioning offers benefits like fault tolerance, scalability, and parallelism.

- Both platforms store messages in order, in a distributed commit log. New messages are appended to the end of the log. This ensures data integrity and gives you the ability to replay messages if needed.

Now that we’ve covered their common denominators, let’s review the architectural differences between Kafka and Redpanda.

Kafka’s architecture

Kafka is written in Scala and Java and runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which means it inherits both the benefits (like platform independence) and the downsides (like garbage collection pauses) of JVM. Kafka is run as a cluster of one or more brokers. Note that you can have multiple Kafka clusters, and each of them can be deployed in different datacenters or regions.

In the diagram above, you can notice a ZooKeeper component, which is responsible for things like:

- Storing metadata about the Kafka cluster — for instance, information about topics, partitions, and brokers.

- Managing and coordinating Kafka brokers, including leader election.

- Maintaining access control lists (ACLs) for security purposes.

There’s a plan to completely remove the ZooKeeper dependency starting with Kafka v 4.0 (which is projected to be released in April 2024). Instead, a new mechanism called KRaft will be used. KRaft eliminates the need to run a ZooKeeper cluster alongside every Kafka cluster, and moves the responsibility of metadata management into Kafka brokers themselves (see KIP-500 for more details). KRaft simplifies Kafka’s architecture, reduces operational complexity, and improves scalability. In fact, KRaft is already production-ready: when you create a new Kafka deployment, you can choose whether you want to run it using ZooKeeper, or using KRaft.

Provided you use Confluent, in addition to Kafka brokers and the soon-to-be-retired ZooKeeper, a Kafka cluster may contain other components, such as:

- REST proxy (which translates REST calls into Kafka client calls, allowing apps to produce and consume messages without requiring a native Kafka client).

- Schema registry (a centralized repository for managing and validating schemas for message data, and for serialization and deserialization).

Finally, a few words about data storage. Kafka has traditionally stored messages exclusively on local disks on Kafka brokers (the retention period is configurable). However, there’s a plan to introduce a tiered storage approach for Apache Kafka, with two tiers: local and remote. The local tier will use local disks on Kafka brokers to store data. It’s designed to retain data for short periods (e.g., a few hours). Meanwhile, remote storage will use systems like the Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) and Amazon S3 for long-term data persistence (days, months, etc.).

The tiered storage approach allows you to scale storage independently of memory and CPUs in a Kafka cluster. Furthermore, it reduces the amount of data stored locally on Kafka brokers and, hence, the amount of information that needs to be copied during recovery and rebalancing between brokers. Note that while tiered storage is in the works for open source Apache Kafka, it’s something that Kafka vendors like Confluent and Amazon MSK already provide.

Redpanda’s architecture

Redpanda is written in C++, offering a high-performance thread-per-core architecture that uses the Seastar framework under the hood. This allows Redpanda to pin each of its application threads to a CPU core to avoid context switching and blocking. This thread-per-core architecture ensures high throughput and consistently low latencies.

Similar to Kafka, you can run Redpanda in a cluster consisting of one or more nodes (and you can have multiple clusters that can be deployed across multiple availability zones or regions).

However, unlike Kafka, each Redpanda node runs the same binary and plays one or more roles, such as being a data broker and/or an auxiliary service (e.g., HTTP proxy or schema registry). Furthermore, each node natively “speaks” the Raft consensus algorithm, which means there’s no need for a service like ZooKeeper or separate quorum (controller) servers (as is the case with Kafka’s KRaft). Overall, Redpanda has a simpler architecture than Kafka, with no external dependencies on components like JVM or dedicated ZooKeeper servers.

Like Kafka, Redpanda stores data in local disks on brokers, and the retention period is configurable. In addition, you can set up tiered storage, which allows you to move data from local storage to object storage for long-term persistence (the supported options are Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage, and Azure Blob Storage). The main benefit of Redpanda’s tiered storage feature is that it enables you to store data in an efficient, cost-effective way. However, it’s important to note that tiered storage is only available if you have an Enterprise license. Otherwise, you have to rely exclusively on local storage.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: messaging capabilities and ecosystem

As shown in the table above, Kafka and Redpanda have a lot of similar/identical messaging capabilities. This is no surprise, considering that Redpanda is compatible with the Kafka protocol (you can even think of Redpanda as a C++ clone of Apache Kafka). I won’t elaborate on all the messaging capabilities listed in the table, but here are a few comments:

- Kafka and Redpanda are suitable for use cases where data integrity is critical, and strong message delivery guarantees are needed (exactly-once semantics and message ordering).

- Both Kafka and Redpanda follow a “simple broker, complex consumer” model. This means that developing consumer apps can be a bit more challenging, but the broker is lightweight, and easier to manage, operate, and scale.

- Both Kafka and Redpanda consumers pull messages from the broker. The main advantage of this pull approach is that consumers can control the rate at which they read messages, without the risk of becoming overwhelmed.

Kafka has a much larger ecosystem of native integrations compared to Redpanda. The Kafka Connect framework allows straightforward data ingestion from other systems into Kafka, and the streaming of messages from Kafka topics to various destinations. There are hundreds of connectors for different types of systems, such as databases (e.g., MongoDB), storage systems (like Azure Blob Storage), messaging systems (for instance, JMS), and stream processing solutions (e.g., Apache Flink). Meanwhile, Redpanda offers around 15 managed connectors, to integrate with systems like Amazon S3, JDBC, Snowflake, and MongoDB.

It’s worth mentioning that Redpanda works with Kafka Connect connectors. However, there is no guarantee that Kafka components behave the same way when used by Redpanda, which is a non-Kafka solution that only uses the Kafka protocol.

Kafka also has the upper hand on Redpanda in relation to native stream processing capabilities: Kafka Streams is a mature, stable library that was first released in 2016. In contrast, at the time of writing (September 2023), Redpanda’s native stream processing capability — Redpanda data transforms — is in technical preview, and not yet production-ready.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: performance, scalability, reliability

Kafka and Redpanda are resilient, fault-tolerant, and highly available solutions. Both platforms allow you to store messages indefinitely. Furthermore, Redpanda and Kafka can replicate data across brokers, which is essential for data integrity and preventing single points of failure.

It’s also worth mentioning that both Kafka and Redpanda support geo-replication, thus ensuring continuity of service even if an entire datacenter or region goes down.

Kafka and Redpanda are designed to provide high performance at scale. In theory, Redpanda performs slightly better than Kafka, because:

- It’s written in C++, which brings some advantages compared to Java. For instance, C++ provides manual memory management with explicit allocation and deallocation. This gives developers the freedom to optimize memory usage patterns. Plus, C++ allows for more direct control over hardware, memory access, and system resources.

- There’s no dependency on JVM or ZooKeeper, which can create bottlenecks and impact performance.

- It’s designed to take advantage of modern hardware, including NVMe drives, multi-core processors, and high-throughput network interfaces.

A benchmark created by the Redpanda team shows that their product offers better performance than Kafka. The benchmark claims that Redpanda is significantly faster on medium to high throughput workloads, and provides more stable latencies. The benchmark also shows that Redpanda needs 3x fewer nodes than Kafka to deal with high throughput workloads.

In response to Redpanda’s benchmark, Jack Vanlightly (Staff Technologist at Confluent) ran his own performance benchmark comparing Kafka and Redpanda, and published a seven-part blog series to share his findings. Here are some of the key points:

- Kafka outperforms Redpanda when the number of producers and consumers increases.

- Running Redpanda for 24 hours under constant load resulted in huge latencies, which was not the case with Kafka.

- Using record keys reduced Redpanda throughput and increased latencies significantly. Kafka performed much better.

- While under constant producer load, consumers only managed to drain backlogs with Kafka.

So, what conclusion can we draw based on these two benchmarks? Well, we should bear in mind that performance benchmarks are often tailored to make one system look better than another; nobody is going to publish a benchmark that shows their product is worse than the competition. We shouldn’t generalize the results of a benchmark and expect they will apply to all scenarios. Therefore, if you’re pondering whether Kafka or Redpanda offers superior performance, you should test them both yourself and see which one offers the best performance for your specific use case.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: developer experience and community

In terms of community, adoption, and learning resources, Kafka is the clear winner. In more than one decade of existence, Kafka has become the de facto standard for event streaming. The Apache Kafka community is vast and active — there are numerous conferences, hundreds of meetup groups, and plenty of tutorials, blog posts, and even books about all things Kafka. On top of that, Kafka is well documented, and there are tens of online courses you can take to learn about it. Kafka is a mature product that’s been embraced and extensively battle-tested by more than 100,000 organizations worldwide. In contrast, Redpanda is an emerging technology with a much smaller community and user base, and limited learning resources. It will be interesting to see how Redpanda will evolve in the following years, and whether or not it will be able to reach the same level of widespread adoption, with a large and strong community, and diverse learning resources.

Things are more balanced when we look at clients, CLIs, and monitoring. Kafka offers a wide variety of clients (both official and community-made), giving you the flexibility to work with your preferred programming language(s) when implementing client apps. This also applies to Redpanda, which, in theory, can work with any Kafka client. Both platforms provide built-in CLI tools to manage your clusters, topics, and brokers. Redpanda and Kafka rely on external tools for monitoring, such as Grafana and Prometheus.

Both tools have a similar learning curve (a few days/weeks to learn the basics, and up to months to gain intimate knowledge about their inner workings). Redpanda is easier to deploy and use in self-managed environments, because each node comes with built-in schema registry, HTTP proxy, message broker capabilities, and Raft-based data management. Meanwhile, Kafka relies on external dependencies (JVM, ZooKeeper).

Redpanda vs. Kafka: licensing and deployment options

Here are a few comments and key takeaways:

- Kafka is available under an open source license, while Redpanda isn’t.

- There are numerous vendors offering managed Kafka deployments and support, giving you the flexibility of choosing the one that best suits you, which is not the case with Redpanda.

- There are various options for running Kafka and Redpanda: bare-metal hardware, virtual machines, on-prem, in the cloud, using Kubernetes, etc.

- Redpanda offers an interesting BYOC model, with the Redpanda team managing the provisioning, monitoring, and maintenance of Redpanda clusters in your own cloud, while sensitive data is kept in your environment. Aiven offers a similar BYOC model for Kafka.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: use cases and which one to choose?

Redpanda and Kafka are distributed data streaming platforms that underpin the same use cases. Here are their most common applications:

- Event streaming and real-time data processing

- Streaming ETL/ELT and integrating disparate components

- Low-latency messaging following the pub/sub pattern

- Building event-driven architectures

- Log aggregation

- Event sourcing

- Change data capture (CDC)

- Real-time analytics

- Website activity tracking

- Metrics collection for real-time monitoring

So, when should you use Redpanda, and when should you opt for Kafka?

Redpanda is a good choice if:

- You have a C++ infrastructure or prefer to work with C++ instead of Java.

- You want to avoid JVM overhead and you’re seeking a simpler, less complex architecture that theoretically offers slightly better performance.

On the other hand, Kafka is the superior choice if:

- You’re dealing with Java/JVM infrastructure or prefer to work with Java instead of C++.

- You want to leverage a richer ecosystem of native integrations and more mature native stream processing capabilities.

- You want to benefit from more learning resources and a much larger community of experts that can support you.

- You’re looking for an open source event streaming technology.

Redpanda vs. Kafka: total cost of ownership (TCO)

Estimating the total cost of ownership for Redpanda and Kafka involves many variables. Self-hosting Redpanda/Kafka means you will have to deal with the following main categories of expenses:

- Infrastructure costs. Includes the servers, storage, and networking resources required.

- Operational costs. Refers to all the costs of maintaining, scaling, monitoring, and optimizing your deployment.

- Human resources and manpower. This involves the costs of recruiting and training the required staff (DevOps engineers, developers, architects, etc.), and paying their salaries.

- Downtime costs. While hard to quantify, unexpected cluster failures and service unavailability can lead to reputational damage, reduced customer satisfaction, data loss, missed business opportunities, and lost revenue.

- Miscellaneous expenses. Additional expenses may be required for security and compliance, auditing purposes, and integrations (e.g., building custom connectors).

A blog post written by the Redpanda team claims that self-hosting Redpanda is several times cheaper than self-hosting Kafka. According to the blog post, Redpanda generally requires fewer nodes than Kafka to maintain comparable levels of performance (high throughput at reasonable latency thresholds), and comes with a lower administrative burden.

While it may be true that a self-hosted Redpanda deployment could help you reduce infrastructure and operational costs compared to self-hosting Kafka, you should also bear in mind that, similar to performance benchmarks, TCO comparisons are often meant to make one system look better than another. You can’t generalize a TCO comparison and expect it will apply to all scenarios and workloads.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that Kafka has a much larger community of experts. Therefore, with Redpanda, you might end up spending more time searching and recruiting staff, who could have higher salary expectations (as Redpanda is a niche technology compared to Kafka).

The TCO for self-hosting Kafka/Redpnda can differ wildly depending on the specifics of your use case, cluster size, and volume of data. The total cost of a self-managed Kafka or Redpanda deployment can range from tens of thousands of $ per year (for small workloads and one engineer on your payroll) up to millions of $ per year (for large workloads and a bigger team).

Of course, you can also opt for fully managed (and serverless) Kafka and Redpanda deployments. The overhead of self-hosting might make managed services more cost-effective, especially if you have a smaller team, limited expertise, and faster time to market is important to you. As previously mentioned, with Kafka, you have the flexibility of assessing various vendors and choosing the one with the friendliest pricing model for your specific use case and usage patterns. In contrast, there aren’t multiple vendors to choose from for fully managed Redpanda.

A brief conclusion

After reading this article, I hope you better understand the key differences and similarities between Kafka and Redpanda. Before choosing one of them as your data streaming platform, I recommend running PoCs, so you can see which one performs best depending on the workloads specific to your use case.

If you’re looking to complement your Kafka/Redpanda deployment with a Python stream processing solution, Quix is one of the solutions you might want to investigate. Quix Streams is an open-source, cloud-native library for processing data in Kafka (and Kafka-compatible tools like Redpanda) using pure Python. It’s designed to give you the power of a distributed processing engine in a lightweight library by combining the low-level scalability and resiliency features of Kafka with an easy-to-use Python interface.

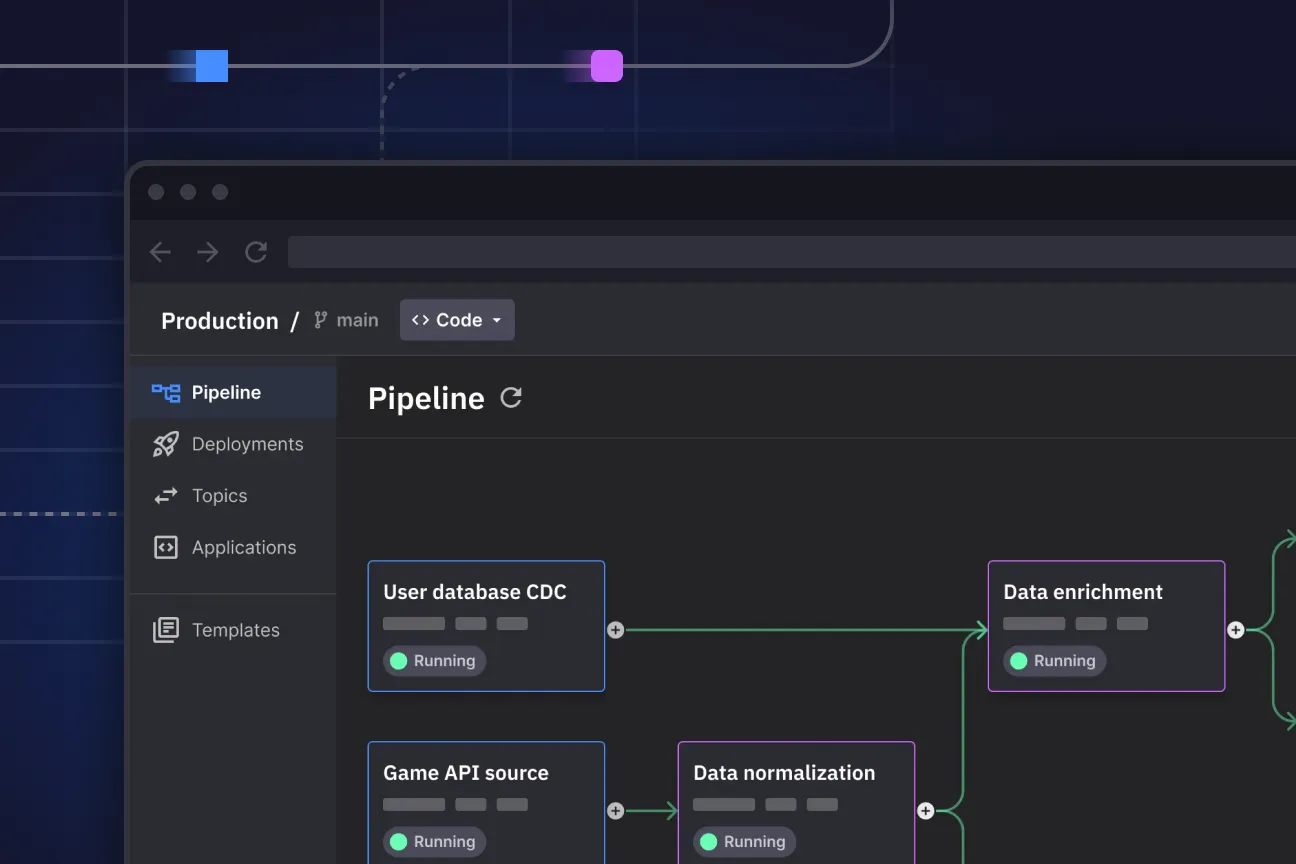

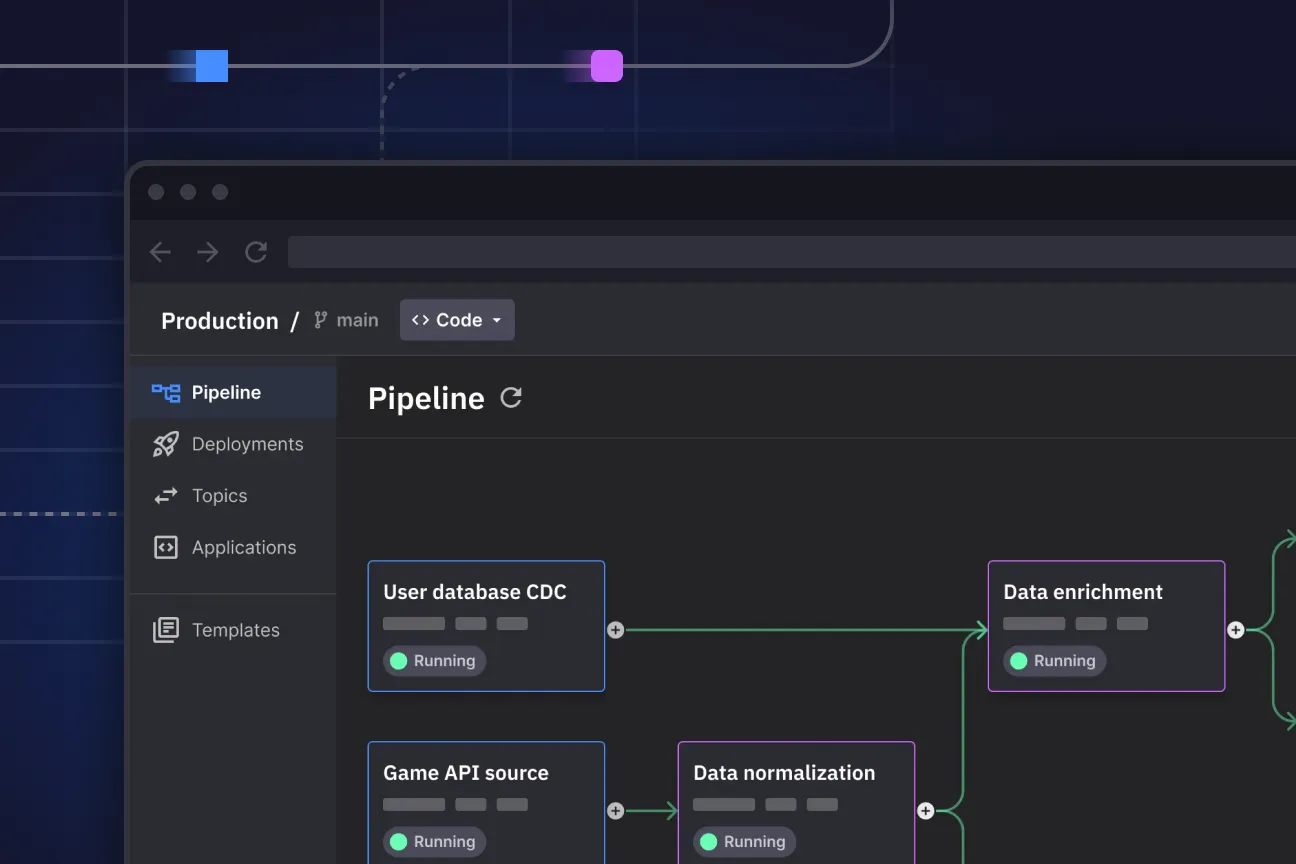

And if you want to avoid the headache of managing a stream processing engine in-house, Quix Cloud has everything you need to build, deploy, and monitor Python stream processing applications in a fully managed cloud environment.

This gallery of project templates showcases what kind of applications you can build when pairing Kafka/Redpanda as your streaming transport with Quix as your Python stream processor. I encourage you to check it out.

Check out the repo

Our Python client library is open source, and brings DataFrames and the Python ecosystem to stream processing.

Interested in Quix Cloud?

Take a look around and explore the features of our platform.

Interested in Quix Cloud?

Take a look around and explore the features of our platform.

.svg)